Last week was Banned Books Week, so to celebrate I read as many banned/challenged books as I could. I spent a couple days sick in bed, so that gave me a little more time.

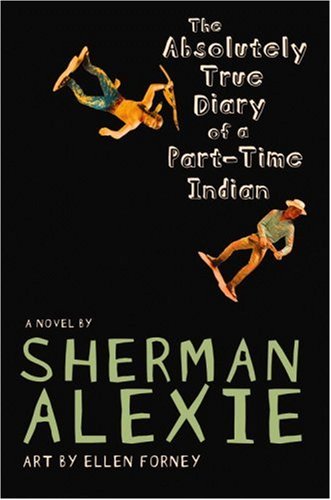

The first and best book I read last week was Sherman Alexie’s Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian. Now since finishing it I read others that I was less wowed by, but my first reaction was to wonder what on earth it was banned for—being awesome? (In case you’re curious, it was apparently banned in some places for containing the startling revelation that it’s pretty common for fourteen-year-old boys to masturbate. Now you know.)

The first and best book I read last week was Sherman Alexie’s Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian. Now since finishing it I read others that I was less wowed by, but my first reaction was to wonder what on earth it was banned for—being awesome? (In case you’re curious, it was apparently banned in some places for containing the startling revelation that it’s pretty common for fourteen-year-old boys to masturbate. Now you know.)

Like a lot of the books on the ALA’s most-banned list, this one is moving and thought-provoking. It follows Arnold Spirit, Jr. as he struggles to take control of his own learning and future opportunities by leaving a third-rate reservation school and attending the non-Indian school in Reardon, the next town over. Junior’s decision makes him a pariah among his Native American peers because he appears to have betrayed them by attending the “white school.” On the other hand, regardless of what successes he has in Reardon, he will always be Other. And so as we experience a year in Junior’s life, we feel the very real tension between loyalty to one’s roots and loyalty to oneself. Would junior be a better Indian if he accepted a dead-end life, or if he embraced opportunities and subverted racial stereotypes?

Junior’s dilemma felt real and true to me because I often feel caught between two cultures myself. I find it difficult to gain acceptance from Latinos where I live because I too-easily pass for Anglo. Just this year, my sixth period spent the first couple weeks of school questioning me practically ever day: do I really speak Spanish? Well, or just barely? What on earth would the color of my skin have to do with my ability to speak Spanish? But I don’t look Puerto Rican or Mexican, so I can’t possibly be a real Latino, right? (And yet, unlike most transplanted Latinos here, I can actually read and write in my first language. So the answer to “How well do I know Spanish?” is likely, “Better than you.”) On the other hand, Anglos around me often feel it’s safe to share their most virulent anti-Latino notions with me because, evidently, I’m one of the “good ones.” And, you know, I have run into people who’ve had problems with my speaking Spanish in their place of business, or held my background against me in other ways.

I never had to make the difficult choice Junior did, but getting it from both sides–and feeling conflicted at times–certainly rang true to me.

A quick scan of the ALA list shows that challenged books are often our most thought-provoking books for young teens. As if parents fear what would happen if their teens became to independent and questioning in their approach to the world. On the other hand, not every book I read last week impressed me as thoroughly as this one did. In one author’s case, I could see what bothered the would-be banners, but I felt that the book I read was pretty weak all the same. Not ban-worthy, just not recommendable. I guess it just goes to show that being banned is no guarantee of quality either.

I like the idea of banned books week, though. I like that making an effort to read those books basically subverts the intentions of those who would ban them. The more we encourage people to read banned books, the more that banning them will result in more attention and more sales. Eventually, those who would prevent others from reading a particular book will find that having dialogue about their objections (or letting a book stay obscure) will work better than trying to decide what other people should be able to read. Win-win.

(Note that I’m not equating parents making decisions for their own children with book-banning. Book-banning is when you try to control what other people’s kids can read, by having books pulled from classes and from the library. I don’t think prohibiting your kids from reading a book is generally effective or wise when it comes to teenagers, but it’s not the same thing.)

Subscribe via RSS

Subscribe via RSS