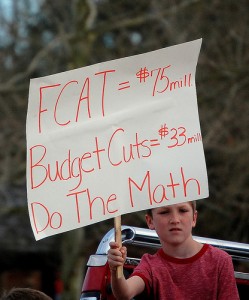

Over the last couple weeks or so, many people in my circles were abuzz over this Washington Post article by Marion Brady relating the experience of a school board member who took a high-stakes test designed for high school students. The school board member reported knowing how to answer none of the math questions (while correctly guessing ten out of sixty) and only 62% of the reading questions, and questioned the relevance of the exams to students’ education, given that he, a successful businessman and public servant, had so little need in his own life for the knowledge tested by the exam. Brady used this as a launching pad for his own opinions on using high-stakes testing as a tool for evaluating teachers, and on how answerable test-backers were to criticism.

On reading this post, and on delving a little deeper into the facts behind this account, I felt . . . conflicted.

Conflicted because I agree that decisions about education policy are being made by politicians whose accountability is not primarily to stakeholders in education, and by politicians who seem in many cases eager for public education to fail, because they see it as but one more manifestation of the evil of big government. (And, you know, by people who have reason to dislike teachers, since they can count on the opposition of teachers’ unions in every election.)

And conflicted because my views don’t run in lockstep with those of teachers’ unions, and the enemy of my enemy is not necessarily my ally. In fact, in the debate over high stakes testing, I’m not sure this Florida school board member is somebody we educators should be rushing to claim for our side.

Here is a little background, in case all you know is what was in the original Washington Post piece, and you haven’t been back to see the updates. First, before making dubious and possibly foolish claims about how arcane the knowledge on the exam is, we might want to look at some of the questions themselves: A sample of FCAT mathematics questions from the Washington Post is here. A sample of FCAT reading questions from the Post is here. More sample math questions, along with some analysis of this case by a college physics professor, can be found here. [Incidentally, I take issue with the slam at “educators” in the title of the Orzel post. I don’t care for the common assumption by college folks that those of us in the classrooms at the high school level and below are ignorant know-nothings.]

For all the FCAT’s many, many flaws, can anybody really claim that the math in question is high-level, esoteric, and irrelevant to most lives? Heck, some of those questions really tested nothing further than one’s ability to read a graph. And—for better and for worse—every single math question includes some kind of real-life context. None is simply an abstract math-for-math’s-sake kind of question. I think any adult who can’t answer any of those questions—none of them—ought to feel pretty embarrassed. More importantly than whether or not he should feel embarrassed, though, is this: if that’s too high a bar to set for our kids, then just what the hell are we teaching them?

For further background, here is a letter to Roach (the school board member in question) from Thomas Singer, an Orange County resident whom I don’t know, and here is Roach’s reply. Marion Brady replied to Singer as well, and you can read his thoughts here.

I think Marion Brady makes some very good points about the multimillion dollar industry that is high stakes testing, and I think he could bolster those good points by looking at Florida Republicans’ emphatic refusal to subject private schools receiving voucher money to the same testing. But I think his points about what kind of learning is and isn’t relevant to the lives of students rests on some very flawed assumptions. In his letter to Thomas Singer, Brady talks about his cousin the engineer, who reported that he could have learned what he needed to know to do his job in a week, and that his education was a waste of time and money. To which I say: Bull.

Not that I don’t believe that he only used a handful of equations in his day-to-day work. But to the idea that the someone without an education would be qualified to be an engineer with a week’s education in a half-dozen equations . . . yeah, that’s a bunch of crap. You could teach a reasonably bright nine-year-old to plug numbers into a complicated equation and get answers; education’s not about the acquiring and memorizing of equations. What education is about is critical thinking skills: learning when to apply this specific algorithm or that one, and understanding where to go look for the specific factoids that you need and don’t recall.

Look, I’m going to spare you my lecture on why what we teach is important. Anybody who’s ever had me as a teacher has heard it. Hell, there’s a whole facebook page where Doug S. complains about how tedious it was to listen to. Instead, I’ll link you to the livejournal of teacher and science fiction writer Jim Van Pelt, who makes pretty much the same argument I always make.

There is pretty much no bit of knowledge that is universally applicable to all jobs, so if that were really our bottom line, we would be teaching a lowest common denominator indeed. The thing is, education is not about inculcating in kids a body of knowledge that they will need in their jobs, but about teaching them critical thinking skills, and teaching them where to go to find the specific bits of information they need. And quite frankly, high school level math is an excellent medium for teaching critical thinking, and deduction in particular.

(As a side note, Brady claims in his reply to Singer that we should throw out this silly, useless curriculum and replace it with “extensive instruction in statistics.” The mathematics on the FCAT is all prerequisite to any kind of instruction in statistics. How can one hope to learn statistics with no knowledge of Algebra? Has Brady or anybody else actually examined this idea, or do we just think it sounds good? Requiring extensive instruction in statistics for high school graduation would actually involve raising the bar and likely failing many more kids.)

To bring this all back around to a point, it’s a really complicated issue, and most of the analysis I see seems to be all yay or all nay, when really there’s nuance here. Yes, I have problems with the FCAT; but I don’t agree that none of the math on it is relevant.

Roach asks the following questions, quoted in the Brady piece: “Who decided the kind of questions and their level of difficulty? Using what criteria? To whom did they have to defend their decisions? As subject-matter specialists, how qualified were they to make general judgments about the needs of this state’s children in a future they can’t possibly predict? Who set the pass-fail ‘cut score’? How?” All of the answers to those questions are fairly public knowledge and a Florida school board member should know them.

On the other hand, yes, I absolutely agree that policy decisions are being made by people who are unaccountable to stakeholders, with end goals completely unrelated to bettering education in Florida.

Most importantly of all, I agree that test scores are a poor way to judge teacher effectiveness, because all I’ve ever seen is that teachers of honors classes have high pass rates and teachers of remedial classes have low pass rates. Teachers of wealthy kids are judged to be better than teachers of poor kids.* I have yet to see a metric that can take into account the varying levels of knowledge and motivation that kids bring in with them, and that doesn’t instead treat kids as identical empty containers.

And so I’m left torn here. Much as I think our legislators are sabotaging public education, I’m pretty sure that someone who says being able to figure out percentages and read graphs is not relevant to adult life is not the champion whose banner I want to throw myself behind.

More than anything else, I think this speaks to the way that our current public discourse sucks the nuance out of all issues and stances. Is my team the one that opposes high-stakes testing as the be-all and end-all of education, the one that thinks we should not be teaching to the test and that the test is an inadequate way to judge both children and teachers? If so, does that mean my team is also the one that believes that teaching math is irrelevant because it’s not relevant to most adults’ lives? Can I belong to one team and not to the other? (And it’s not just in education: Can you be a Republican and still favor gay rights? Can you be a Democrat and be pro-life? Does it seem like our soundbite society forces people to pick a side and be married to it in all things, lest you accidentally lend support to the other team?)

*Disclosure: I have a 100% FCAT pass rate over at least the past two years. And I work at an A school. Florida Republicans would therefore probably call me a master teacher, no?

Subscribe via RSS

Subscribe via RSS

5 Responses to No Test Left Behind